This essay by Tara Shafer appeared originally in Brain Child Magazine.

My second child was stillborn ten years ago.

A decade out from loss and this is what I know.

When a sonogram showed no heartbeat, I understood I had to deliver my baby.

If I try hard enough I can put myself back there, but I can’t stay. The horror of the moment makes me resist. It propels me like a magnetic force or a backdraft – away.

That day I was admitted to the hospital. I lay in Labor & Delivery stoned on Valium. I was in labor with a dead baby. I remember falling in love, observing great beauty, and getting my heart broken.

I looked out the window at the orange glow of urban pollution against platter-sized flakes of snow that made up a muffled, peaceful hush drifting upwards like specters.

Time was vaporous. I had been induced to deliver with Pitocin. My body had come undone. I waited for contractions to start.

I cried for my dead son. I cried also for my two-year old son, Reid. He had never been away from me and now we were forced apart without warning. That morning he and I had walked through the Central Park Zoo. We passed the carriage horses on the way to a medical appointment, and Reid watched them eat oats out of big buckets.

I closed my eyes. These children. I did not know how to occupy both the lands of the living and the dead. I could not be in two places at once. I looked at my heavily pregnant stomach. Then, I remembered the little red sweater Reid wore when he waved and left the room, glancing backwards.

I can no longer remember the sequence of what happened or when. What I remember most vividly about my son’s (still)birth is playing with the edges of things – discovering all sorts of peripheral realities where death meets birth.

As I labored, I imagined stranger hands on him. He was mine but I could not keep him. I tried to imagine this infant, alive, asleep at home.

On television that night, John Lennon was being over-remembered on the anniversary of his shooting. Lennon singing Imagine was on news clips over and over again. I was drawn to the tinny end-of-the-world music box quality of the song.

After many hours, my baby was born. We named him Dylan. I did not even anticipate the sound of crying. Still, the silence was shocking. In the room there there was no one talking. My devastated husband Gavin was there. The nurse readied the receiving cart but without a sense of urgency. She was somber and deliberate in her movements. She swaddled him in standard issue hospital blanket and put a hat on his head. She looked more like an undertaker than a nurse.

In holding my son, I was aware that there would be no second chances. I did what I could to stay present even as I left behind the life I had been leading until that point.

After a while, someone (I don’t remember who) asked, “Are you ready?"

I suddenly understood what it would have felt like to give up a child for adoption when adoption was secret and mothers too young. You hand your baby over.

As I did. But I knew he would never grow up. He would never find me.

“Are you ready?"

It is a terrible way to phrase this question.

We cremated our baby. We returned to our life with Reid. We tried to figure out how to explain the death of a baby whose existence had had never known to a young child. A play therapist assured us that young children do not see death as either permanent or negative. Several days later, we explained that the baby would not be coming to live with us. That night as I lay in bed, soapy softness wafting off of him, I asked Reid whether he would crawl back in to my stomach and be a baby once more. Not my finest moment as a mother. He answered, “yes Mommy, so I could die and die and die."

When we tried again, sex was multi-faceted. It was recreational, procreational, and post-traumatic.

When we did get pregnant again, I had difficulties processing this reality. I took Reid to a nearby orchard and sat we sat there. I tried to understand that the coming months would be living moment to moment. I thought about the fear I would face as I waited for fetal movement. I thought about how this was the gift of another chance. I considered this all under the kaleidoscope sky with the apple trees, and the earth smell of fall everywhere. There were creeping early shots of colors in the trees as they prepared to burst into color and then retreat – a half death – until the spring. I looked at the weeping willows tacked up perfectly against the blue fall sky settling down from the scorch of summer; the world around began to recoil temporarily.

Reid grounded me, and I had to let him.

I hid the fact of pregnancy for an absurd amount of time. Depending on the moment in the day, I loved or tolerated or survived this pregnancy. I learned to exist in crisis mode. Phone calls made me jump. It began to feel like alarmist Zen. I did weekly non-stress tests at the hospital. I gazed upon my baby on an ultrasound screen in sanity-saving weekly ultrasound appointments. He was so near and so far. I could grow him, but I could not save him if it came to it. I was more voyeur than mother.

These were hard months, but so too, were they full of grace.

As the days before birth approached, I found I could not stay present. There was a biblical storm and the rain came down in sheets. Non-essential travel in New York State was officially discouraged.

We drove slowly from upstate New York to the city hospital on the flooded roads that were looking delta-like. There were houses sticking up through water. I half-expected to see destitute children sitting atop roofs without shoes. I glanced at Reid in the rearview mirror, and I thought about his sustaining love and how he could never know the impact of his presence. I was shocked at the finality of and the force of regret I suddenly felt at what will be lost between he and I.

As panic at the thought of the alternative rose like bile within me, I tried to steady myself. I told Reid how very much I loved him.

He looked into the rearview mirror and placed his fingers on his eyebrows and moved them around.

“Mommy?" he said. “Did you know that my eyebrows look like corn cobs when I do that?"

At the hospital, my husband and I stood outside in the early spring wind, blows dampness around imagining the promise in existence everywhere. People walked by, hospital staff stood smoking in scrubs, the lights of a diner flickered. I remember thinking that I had never seen anything more beautiful than this. The rain was stopping, but rainbow colored oil slicks ran down in rivers towards gutters on the city streets.

The next day, my son David was born, and they put him on my chest.

He was so small. I had forgotten what newborns felt like and how much like a petal their skin is.

I lay there, an infant at my breast, and I again recognized that humans are frail. There is honor in trying to become strong.

A few years later, another baby would be placed on my chest. This one would be a girl. Isabelle, like her brother, would be born in a snowstorm. However, she lay next to me fully in my possession.

My family is growing up. I can’t even believe how old my children are now as they set their courses. I try, as all parents do, to provide perspective. At the Haydn Planetarium, there is a plaque that describes the potential for interstellar life and how little we know yet about galaxies. Part of it reads: “The stars in the sky seem permanent and unchanging because it takes millions and billions of years for their lives to unfold."

I have a memory from childhood. There is nothing significant within it except that I understood something abstract without being told. I was walking with my father once in mid-winter at dusk. The snow was blue against the winter sky, and the embers of the orange light were fading and strewn across the sky. The blueness of the snow looked like the sea but perfectly still, beautifully captured, imprisoned and resolute. It had stored the light from the sun, and it was still there within, beneath despite the general appearance of death, of nothing stirring. My father told me, “This is the harsh beauty of winter."

I understood that the scene was both beautiful and harsh and that these two things could easily be fused. What is absent can be just as glorious as what is present. On that rising hill beneath the sky, there was lots of life, but it was suspended, waiting. The winter was the victor there, and it contained much in the way of dormant things all trapped within it. For all that winter freezes, it coats and protects.

Without all that is absent – what is taken from us – we do not know the truth about what is present. These losses, these tragedies, provide a context. They give the gift of hard-won self-knowledge too important to bury or obscure.

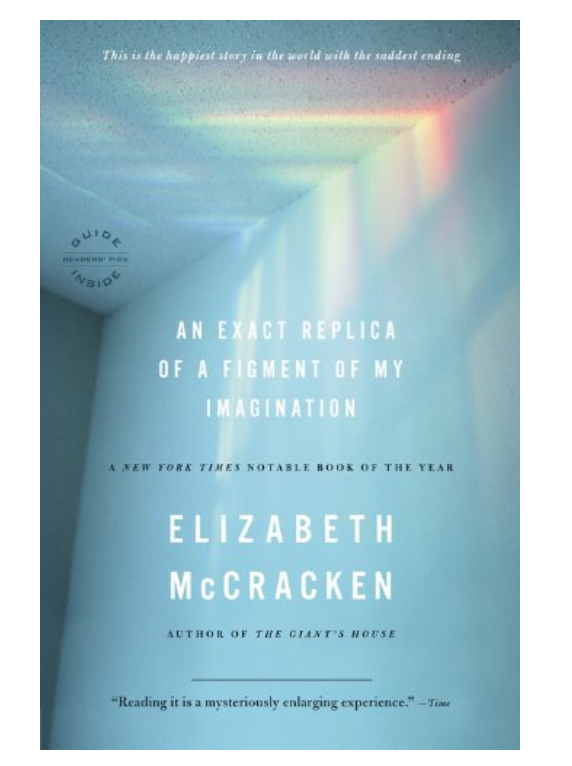

Helpful Products

Give InKind does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. We have an affiliate relationship with many of the advertisers on our site, and may receive a commission from any products purchased from links in this article. See Terms & Conditions.