Give InKind is pleased to feature Michael Ravitch whose work has appeared in many publications including the New Republic.

The cemetery where he is buried has the ample dimensions of a public park and the elegance of a painted landscape: horizons disappearing around gently curved roads, sloping hills, marble mausoleums in the shapes of miniature Gothic churches and Roman temples. Here lie the founders of Akron, Ohio, the barons of the tire industry, their stately circumstances befitting their own sense of entitlement.

Nowadays, however, post-industrial decay is eating away at this island of suburban grandeur, waves of neglect coursing over the edges of the graveyard. In every direction through the crumbling fence you can see unpainted clapboard houses, overgrown yards, rusty wire, open garbage, the detritus of the vanishing rubber industry, a tide rising against the privilege of the fortressed dead.

The funeral director takes pity on us because of the unseasonal snowstorm and takes us in his car to one particularly neglected corner of this vast field, the section for stillborns. It is called “Babyland."

Here is where I will leave him, what remains of him, all there ever was of him, here in this strange city.

Trudging through the snowstorm, our weird band, we two gay dads, plus the husband of the surrogate, plus a young woman Rabbi we had found, there to bury what we had brought into the world, wrapped in a baby blanket, with a stuffed animal for eternity, the four of us saying the mourner’s kaddish, although it is not officially permitted to mourn a baby who has not taken a single breath.

A prenatal ultrasound early in pregnancy gives us a glimpse of a world we’re not supposed to see. Like the surface of the moon or the bottom of the ocean. A place we know is real, but beyond our earthly existence. A place so far, or so close, no one can see inside. Let there be light, but not everywhere, not until now, and now these distant dark inside spaces can be seen.

Its strange angles and perspectives. A circle at the core, the destination, the vantage point. And then expanding outwards, up and down, forward and back, shifting sands, waves of sound, motion, time and perception.

Think of it like a storm – a doppler map of a hurricane – and in the middle of that storm, think of this tiny sleeping creature, oblivious to the gale force winds, the blinding rains, the constantly shifting surface on which it sleeps.

Hanging on to the surface of the uterine wall, I think, clinging for dear life.

Even when someone explains to me that the growing fetus is in fact held close by the folds of the uterus, snug, burrowed deeply, I still cannot shake the sense of how vulnerable it is, how alone in its struggle to differentiate myself, alone on the difficult road to be born. And now we all have a window on this struggle, we can watch it, noses pressed to glass, an impermeable barrier. Soon it will come into our world, where it will rely upon us for everything, and yet now there is nothing we can do to help it, no way for it to hear us.

I swear I can see it on my friend’s face sometimes – a flicker, a thought of his stillborn son, a small shadow – and then I can see right away how he stamps out the spark. I hear him say to me (all in my head): “I have a wonderful wife and two beautiful girls. How could I possibly complain?"

I have the same voices in my head, the same imperatives: Minimize. Suck it up. Keep it to yourself.

There is a hierarchy of suffering. There is a justified need to rank tragedies. My parents lost a 2-year-old son to leukemia. That was incomparably worse than our child who died in utero, at 20 weeks.

Was it even a “child?" Does it merit that term? What are the right words to use? For that other place – that lunar ocean – we lack words. No gravity on the moon; no working words.

His wife and I have cried together, but my friend has never spoken to me about his feelings – even though he knows we experienced a similar loss.

Rarely does one hear fatherhood spoken of as a longing. Pregnancy is supposed to be the exclusive province of women; they grow the baby within their body; nothing a man can feel or imagine can come close to that. And the pain of feeling that life snuffed out – of nurturing something with your bodily essences – and feeling it die inside you – how can a man’s experience compare to that?

I sometimes think of the unrealized dreams locked away in storage closets in my mind, buried deep, but flourishing there, as if they lived in some alternate world where they had indeed come to pass.

Books I meant to write.

Friends I meant to keep.

But most of all – a little boy. He would be two now, chasing after his big brother, who would yell at him not to touch his stuff.

Sometimes I think Es Muss Sein, as Beethoven said, it had to be as it is, fate is always right and our only choice is acceptance, and then other times I think the membrane between the world of the real and the world of dream is much thinner than anyone realizes.

The first pregnancy was like a movie we produced, with complex spreadsheets and highly technical turning points, featuring a huge cast of actors – multiple lawyers, reproductive endicronologists, an egg donor, agencies, a gestational surrogate, not to mention her husband and children. It turned out to be, in nearly every part, a comic movie, with a few absurd moments, and funny characters, much warmth and love, and a happy ending for all.

We mostly didn’t tell Elijah over the years about our different attempts to have a second child. I remember one morning, when he was three, all three of us snuggled up in bed, I asked him how we would feel about a little brother or sister and he took a long pause, thought seriously for a moment, and then said, “I would love that more than anything in the world."

Still – we didn’t tell him when we finally succeeded after 3 years of trying. One of us flew back and forth to Ohio where Karen lived (the new surrogate) for doctor’s visits. He knew her, had spent the weekend with her children, but he didn’t know about the baby until the weekend before the anatomy scan at 20 weeks.

It was safe to tell him now, we decided. We had had a couple of painful disappointments en route, but we were certain that fate was on our side; we banished all doubt. With great fanfare, we told him that the next day he would get to see his little brother or sister.

It was a brother, as it turned out. A little boy.

It had been a cheerful day. We had lunch with Karen, drove with her to the doctor. The nurses joked with Elijah about becoming a big brother. The nurse rubbed the gel on her large, hard belly and started looking for the baby. Everyone was laughing, hopeful. But when she found the fetus, there was a pause, then the nurse said:

“Let me go get the doctor."

When I remember that moment, I imagine a beachgoer who looks onto the horizon and sees an enormous wave – out of nowhere – the calm atmosphere belying what you sense is about to come, imagining and denying the worst at the same time – sixty seconds of waiting for the doctor to appear, paralyzed and speechless, watching the wave build.

Then the doctor, without any hesitation, almost matter-of-factly, “I’m sorry. The baby is dead."

Instantly the wave breaks: loud sobbing from Karen, and before I can even react, Daniel swoops up Elijah and takes him out of the room. I am frozen amidst the commotion.

Four-year-old Elijah crying outside “But I wanted to be a big brother!"

What was striking about the response of our friends and family was that people needed to justify it. As if the most important thing at the moment was not to express sympathy but to assert that the world was a rational place. Statements like, “Clearly it wasn’t meant to be.. Better that it happened now than later.."

As if it were a miscarriage because of a birth defect, a baby never meant to live.

But we found that out that this little boy had strangled himself on the umbilical cord. Which didn’t make much sense. It had no logic. Nothing Karen had done, nothing we had done. Just a careless boy playing with a cord.

All I could think about at first was how to make this right for Elijah. My own pain I couldn’t feel at first in the presence of the great worry that we had hurt our little boy, our only boy remaining. Later I wondered if the doctor could have been gentler. If he could have suggested that we remove Elijah from the room? Perhaps this was a banal occurrence to him; there was no way he could feel how much wish we had put into this baby.

Within about ten minutes Elijah’s cries of ,"I wanted to be a big brother" changed into, “I want Tootsie Rolls" but with the same plaintive urgency, the wounded injustice children can channel, with no sense of relative importance.

The strength of children: they do not rank their tragedies.

That turned out to be the question on which all my feelings turned – had a soul quickened and come to life? Or was it something that had never happened? It felt insulting on the one hand to confer upon it the status of a life – insulting to the life of children who had smiled, cried, breathed air. And yet so much had happened, at twenty weeks, he had bile, he sucked his thumb, it seemed impossible to dismiss.

And not just twenty weeks of pregnancy, but the three years of trying before that, so many events, so many people, so much good will as well as stress and effort and worry, all of that went into who he was. Our stories don’t just begin with birth, not even with conception in some cases, so much fantasy and hope trailing behind this little being – perhaps more than he could bear?

We had offered to drive Karen home, but she insisted she wanted to be alone. Then we offered to go over there for dinner, as we had originally planned, but again she said she just wanted to be alone with her husband and children. The next morning we had tickets to leave early. As the week passed, the shock didn’t wear off exactly – instead it deepened. Karen chose to induce labor rather than get a D&C. It was scheduled for the next weekend, and we flew back for that, leaving Elijah, for the first time overnight without us, with my mother.

There is a tendency to read backwards from tragedies. As bizarre and arbitrary as they seem at first, they can seem inevitable from a certain angle. It was true that something hard to explain had never worked between Karen and ourselves. We had had a wonderful experience with surrogacy the first time around; she had had a good experience giving birth to twins for another couple. But our personal connection had never felt easy, it had always been awkward, and while I usually pride myself on being able to forge connections with people, I could never quite succeed with Karen, no matter how much time we had spent together.

In retrospect, there is a part of me – the blame-seeking part, that wonders if this failure doomed our child, that if we had all found a way to connect, or realized early on that we didn’t connect and given up, that this could have been avoided.

Karen had spent the week in agony, a special kind of hell reserved for carrying around a child you know is dead, and what she faced over the weekend was even worse: the “birth" of a dead baby, an almost 48-hour induced “labor" in the hospital, with all its attendant suffering, without any of the hope or expectation which can make labor pains easier to bear.

I’m not sure what happened – it was like she couldn’t bear to see us anymore, perhaps her disappointment was so great, her pain so overwhelming. She didn’t want us in the hospital room with her, so we waited outside. Whatever our individual faults, this event somehow exposed the bankruptcy in our relationship. It might have been easier if we had gone through it together – grown closer because of it – but instead we just felt more alienated from one another.

When it was all over, she slowly receded from us; eventually she stopped returning our emails.

There was this ghastly waiting up all night, like a parody of waiting for a birth. The body refusing to give up its precious cargo, fighting to keep the corpse inside. And we the daddies waiting for our baby to be born, waiting outside for this metamorphosis to be over, this first and final act of his life.

How to describe the sight of him wrapped carefully in a blanket we had brought from home? I could only hold him for a minute, so light, a pound, almost nothing, like a clever doll someone had made. He was developed enough to look like a tiny baby, all potential, all the makings of a life lacking one crucial element – the fact of having been born. So light but such a heavy feeling holding this creature and uncanny – I had never held a dead body before, death had never happened right in front of me like this. Daniel held him without pause, so much less inhibited is he about expressing his emotion. Hours passed with us sitting there, weeping copiously.

Then we had to move. We had to get back to take care of our son at home. Ohio law required that any fetus born after 20 weeks be buried. We found the funeral director, the cemetery. We drove him over to the cemetery ourselves, his body in a box at our feet. We walked through the snowstorm, found a hole in the ground prepared for us, covered him with dirt.. out of the ground we are taken, and to the ground we will return…

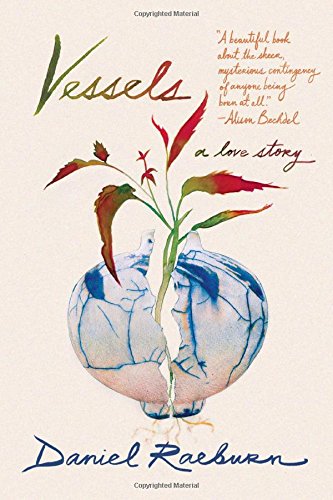

We named him “Lior" – Hebrew for “my light." He had lived his whole life in darkness, so we thought in his name at least he could have light.

Some concerned friends had urged us not to go back to Akron. How different it would have been if we hadn’t seen or held his body. If Karen had chosen a surgical procedure, maybe we could have conceived of it more as a disappointment than a death. But once she had chosen to go through labor, how could we not be there by her side? And then we felt we owed it to “him" – whatever he was at this point – a spirit, a promise, a part of a being. So we went back to Akron; we held him; we buried him.

He had a face – the beginnings of one. I wish I could say he didn’t, but I saw it.

What you see and what you feel are the things that happen to you. They make up who you are. When you are young, you imagine life as only growing and acquiring and gathering. You cannot – at least I could not – imagine the memories you wish you didn’t have, the wounds which do not heal. As you get older, what will happen, has happened. This is part of your story, these scars, this cemetery in this strange city, this baby – this not-yet-a-baby – always there, forever there, never there.

One thing Daniel and I have in common is a pervasive fear that the world will disappear at any minute – a lack of faith in the reality of things unseen. So that if someone we love turns the corner in front of us, a voice is whispering that they will be hit by a car, or disappear. When you suffer from such a morbid imagination, you learn to keep it to yourself, a secret fear flickering at the edge of consciousness. And you always remind yourself how wrong this fear is, how many corners have been turned without disaster, how many airplanes did not crash. But still – despite all rational evidence to the contrary – you can’t help but steel yourself always, trying to defend against this imminent disaster, ready for the bad news. The worst thing would be to caught unaware.

And yet we were. That moment in the doctor’s room, when no heartbeat could be found, we were not ready for. Without a hint of trouble beforehand, this child – the idea of a child we had never seen or held – had died. We had – perhaps for the first time – forgotten the possibility of tragedy, allowed ourselves to trust in the blithe assumption that it would all work out easily – and then what a shock in those few seconds to realize that the baby was completely and utterly gone, there was no reprieve or second chances.

When Daniel and I decided to have a family, we agonized about how to go about it: adoption? Surrogacy? And even once we decided to pursue surrogacy, every decision felt so consequential – should we use an agency? The wrong decision felt like it would imperil the imaginary children.

Then a friend told me about the Tibetan idea that souls bounce around the atmosphere, drawn to a family to be born into. So that it didn’t matter whether we sought to adopt, or have a child from surrogacy, who we found to donate eggs or carry the baby, that if our child was out there, he would find a way to us. Even just construed as a metaphor, I found this immensely comforting, it took away the enormity of our decisions. What would be, would be.

This conception felt good as long as everything went well, but it turned on me when things went wrong. If the creation of this creature – this bit of consciousness broken off and individualized – had any meaning, then what did it mean that it departed so abruptly?

Had we said the wrong thing? Had Lior seen through to our secret flaws?

On the one hand this could be considered just an arbitrary event. Sad, disappointing, tragic, but simply a random accident. Pregnancy involves risks, and we had fallen afoul of the odds.

On the other hand, there was nothing accidental or happenstance about this pregnancy, we had been obsessed for over three years, imagining him, bringing so many other people into our effort to create him, like witches over our pots – aided by helpful others, a circle of women, singing around us and encouraging us and lending their bodies and their love, all the characters in our strange post-modern saga, all of this energy bringing his spirit down.

I am reminded of this line from Goethe’s “Faust":

“I possessed the power to summon you but not the power to make you stay.. “

Why could we call him here and yet not make him stay?

So do I need to mourn what I never knew? Do I have the right to?

There are increasing numbers of us, parents by imagination, fathers of course, but mothers also, for whom parenting is first an act of will and desire before it is a biological reality. Somehow it feels like a woman who bears a child has earned the right to parent, while for the rest of us, our claim to the title seems more provisional, something we have to earn.

I imagine there is some small comfort, even in the midst of the most devastating loss, in what you remember of the lost one. There is a rock-bottom certainty to absolute grief. But this kind of awkward inbetween loss – a life mourned which had never started – is hard to explain and isolating.

I cannot shake the sense that someone existed, something beyond myself, beyond my hopes and fantasies, even if it was just the slightest phantom of a person, a shadow of a ghost.

He has a name, he has a grave. We saw his face. These things were real. He has left his trace on me, like a fossil embedded in my flesh.

He never existed – but he still exists. I have nothing to remember, and yet I can’t forget.

I can’t quite put him out of me.

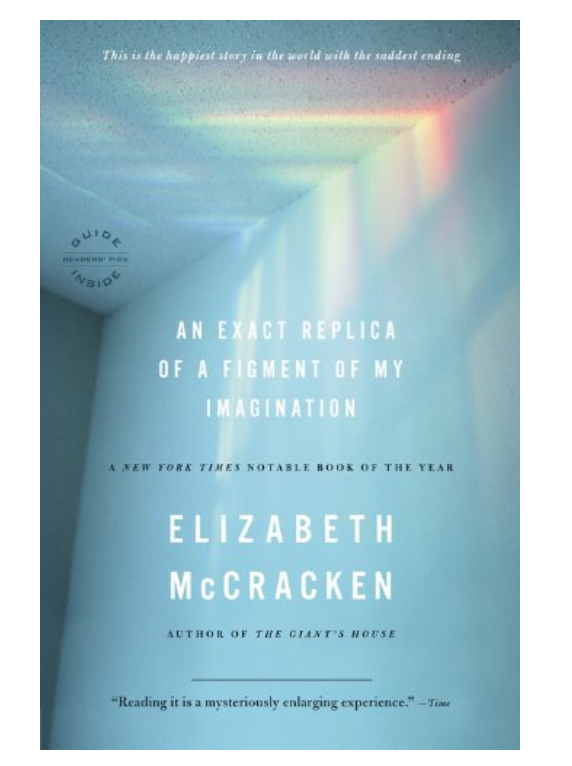

Helpful Products

Give InKind does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. We have an affiliate relationship with many of the advertisers on our site, and may receive a commission from any products purchased from links in this article. See Terms & Conditions.